Problems and chances of a reenactement

Judith Engel, Freelance Cultural Journalist and Author

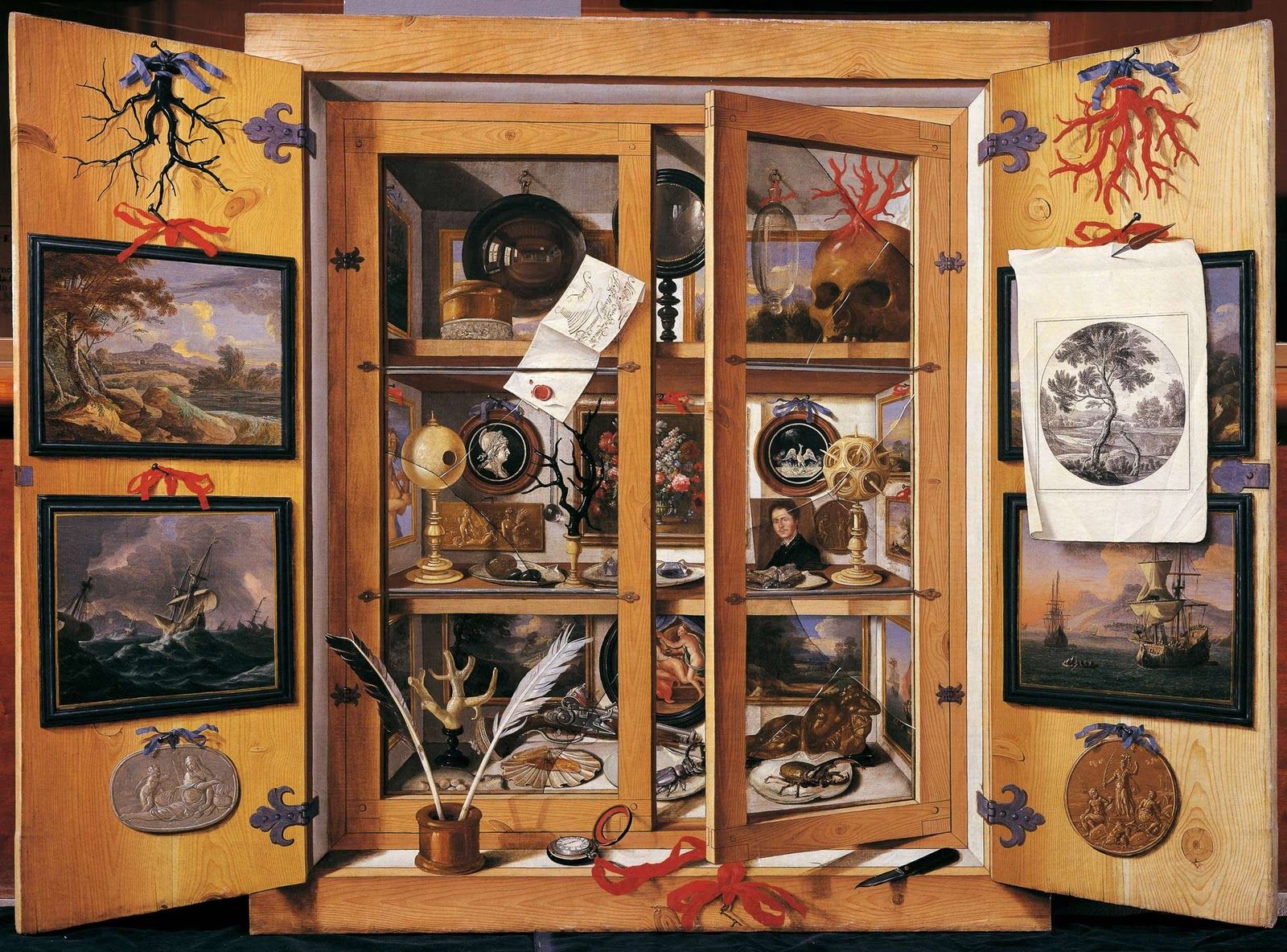

The world shows itself as a heap of pretty junk, when one lacks the order parameters. This is roughly the conclusion of the overwhelmed author Jean de Labrune, who reports on the baroque Wunderkammer of the Basel collector Remigius Faesch from 1686. He comments that it was hard to keep track of that peculiar collection, which contained curious objects of solid value, questionable objects such as a very thin piece of wood, and hardly any special stones. According to subjective taste criteria, a man with fortune had assembled an untidy collection, about which one could simply “marvel”. Nobody had curated them.

2021 is not the best time to proclaim a renaissance of wonder. It is difficult to see the world today as a place of wonder: the economic, social and ecological consequences of centuries of Western capitalism are emerging with clarity, and rarely has the world seemed as disenchanted as it does at the moment. Nostalgia is misplaced in the context of this historical comparison. For all one’s love of rarity, one admires the status of the collector at least as much as the collection itself: in the 17th century, it was not the world that was more astonishing, but merely astonishment that was an appropriate response to the celebration of male privileged demonstrations of power. Thus, the attempt to rehabilitate the Wunderkammer does not exactly suggest itself. What, one must ask, could be interesting about dealing artistically with this early phase of museum history? Why take up the idea of showing different positions, objects, art and non-art side by side, uncategorised, in four display windows? Can this setting of a dusty collector’s passion for the European upper class be made artistically and critically productive for a modern audience?

It is perhaps precisely the problematic nature of the concept of Wunderkammer that can be made fruitful for a contemporary reflection on representation within the world, if one dares a kind of reenactment that is both a funeral and an experimental arrangement. A funeral as during the 17th century, a self-awareness of male-western superiority began to emerge, even if the climax of colonial exploitation was not reached until two hundred years later. This is evident in the self-aggrandising idea that the world is a place in which wealth is open for the taking. The fact that this self-service at the buffet of wonders was reserved for only a few wealthy white princely sons was given little thought, and if it was realised, it was without a guilty conscience. On the other hand, (this being a cautiously formulated thought) this germinating hubris of Western fantasies of superiority was still scattered in the cabinets of wonders somewhere between comet splinters, mechanical clocks and rare feathers. Under the pretext of the astonishing, the valuable was found here almost without hierarchy next to the worthless. Natural objects next to handicrafts, everyday objects next to curiosities. The juxtaposition of objects, whose peculiarity made a clear classification impossible, is a way of looking at the world that changed radically with modernity and the rise of the natural sciences and the resulting separation into nature and culture. Whereas 300 years ago, amazement was the socially acceptable response to the costly performance of the wealthy and well-born. Modernity puts knowledge and recognition in the place of this naive fascination borne of privilege. One no longer collects indiscriminately, but sorts the world systematically in ethnological museums, natural history museums, zoological gardens and world exhibitions. One is no longer enchanted, but wants to rationally see through the cosmos: it’s evolutionary and ideological order, incidentally placing oneself as a Western European “scientifically well-founded” individual at its peak.

In contrast, the unseparated juxtaposition of art, non-art, utilitarian object, and natural object really seems like a contemporary exhibition concept that questions these structures of order. A place where, although collected, a potted plant stands next to an artisanal object with equal authority and is not categorised in terms of value. In fact, the purpose of these collections at the time, was to represent the universal connection of all things, with the aim of conveying a worldview in which history, art, nature and science merged into a singularity. However, the last 300 years have repeatedly shown that the idea of unity can never be thought of without the other, through whom this unity first manifests itself. The Wunderkammer, despite the democratic exhibition of the objects, sought out curiosity in the world as it was. It was not about altering a state, it was about marvelling at the world and at the status of the collector who had assembled this universe. This unreflective amazement and the collection as a status symbol, that has to be buried.

Nevertheless, it can be worthwhile to go back to this problematic place. To assert an equal coexistence of man-made and nature-made materialities for the time being, that can be a daring experimental arrangement as an artistic-political attitude and not as a demonstration of status.

Part of this experiment is also the choice of location. In the shop window of a street parallel to a pedestrian zone, the Wunderkammer becomes a public event and no longer shines with exclusivity. Here, all passers-by casually gaze at what is on display, which cannot be acquired or owned as an individual piece of a collection or as a commodity. This also changes the action of looking. In the best case, it is no longer an individual looking at a collection of objects that represent a unified world. Rather, it can be a matter of attempting a Wunderkammer in which the things themselves cast back glances: either the glances of those who created them or of the cultural heritage to which they pertain. Not to create unity, but to insist on the abolition of disciplinary boundaries and separations of the artificial and the natural, that a duality of looking is made possible. A reflection on things that are not ready to submit to the imagination of a collector. A change of gaze between object and those in-between. A looking at things that are not ready to enchant individuals, but that demand their own gaze, conversely turning the Wunderkammer and its history into an exhibition object.

Judith Engel

She studied at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart and is currently finishing her master’s degree at the Merz Akademie Stuttgart in “Research in Design, Art and Media”. In addition to realising her own artistic projects, she develops essayistic and literary texts, mostly in cooperation with other artists and in response to their work. Since 2013, she has also been writing online and offline about theatre, art, and performance art. In 2016, she was a fellow at Akademie Schloss Solitude, where she provided editorial support for the Schlosspost online platform until 2019. She is currently working with the artist and director Sabrina Schray on the theatre piece “I Say I Shoot You, You Are Dead,” which is supported by Freischwimmen-Förderung.